KUTNÁ HORA: silver and bones

Kutná Hora is an ancient town located to the east of Prague, an hour journey by train, and which is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Though in medieval times it was a a mining center that contributed significantly to the royal coffers of the princes of Bohemia, these days it is probably best known for it’s macabre ossuary, a bizarre sepulchre which holds the artfully arranged remains of an estimated 40,000 to 70,000 corpses; and also for its well-preserved Gothic architecture as represented by the churches of St. Barbara and St. James, and many other surviving buildings from long ago. If you’re looking for a day trip out of Prague, Kutná Hora is a worthwhile and interesting destination.

The Church of Saint Barbara. Photo Jerzy Strzelecki

A Brief History

Silver production existed in the Kutná Hora area at least as far back as the 10th century, though sophisticated mining practices and a mining industry didn’t develop until many years later. The settlement began moving forward around the time of the foundation of the Cistercian monastery at Sedlec in 1142 which was undertaken by monks from the Waldsassen Abbey in Bavaria. With the discovery of rich veins of silver, German miners and prospectors began moving into Kutná Hora during the 13th century bringing with them both their technology and their culture, and establishing a loose structure of disorganized, unregulated mines that had no township rights. Then in 1300 King Wenceslas II issued the Ius Regale Montanorum, his new royal mining code which set forth the technical and administrative regulations pertinent to mining operations, and this allowed Kutná Hora (or Kuttenburg, as the Germans called it) to become a political entity. Shortly thereafter the main mint for the Czech lands was established at the Italian Court in Kutná Hora, and then the influx of riches from the silver trade set the former rough mining village on a path to becoming the late Middle Ages’ second most important city in Bohemia after Prague. Throughout the 14th century, bigger and better stone houses began to replace wooden structures within the city’s wooden walls, and soon even those walls were replaced by proper ramparts that enclosed an area so large it was only rivaled by Prague’s Old Town. During this time were built the brilliant Gothic churches of St. Barbara and St. James, as well as a hospital and an expanded merchants’ district.

But in the early part of the 15th century Kutná Hora began to fall on hard times with the advent of the Hussite Wars. The largely German patriciate of the city backed the Emperor against the Czech Hussites, who in the end were able to drive the Emperor’s armies away from the area. The monastery at Sedlec was captured and burned, and many German miners were forced to leave the area. The years following were marked by two enormous fires that devastated large sections of the city, and then all mining operations came to a standstill for several decades, not to be restored until the 1460s when Kutná Hora once again became a flourishing center of activity. However, by the early 1500s the city’s mines reached to depths of 500 meters and, though their output remained respectable for another hundred years or so, the silver veins were beginning to run thin. The following century the region was hit hard during the 30 Years War of 1618-1648, during which it was twice sacked by the Swedes, who caused extensive damaged which was never completely repaired. The city was then crippled by punitive tax burdens after the war, levied by the Hapsburg monarchy of the Austrian Empire which was by that time in control of the Czech Crown lands. By the time the silver industry was able to pull itself back together in the early 18th century, the major veins were almost exhausted, and what silver remained was buried far below the surface and thus very costly to extract. One by the one the mines began shutting down, and Kutná Hora’s glory days became forever a part of the past.

The Sedlec ossuary. No dogs allowed. Photo by Marcin Szala

Hundreds of Thousands of Bones – The Sedlec Ossuary

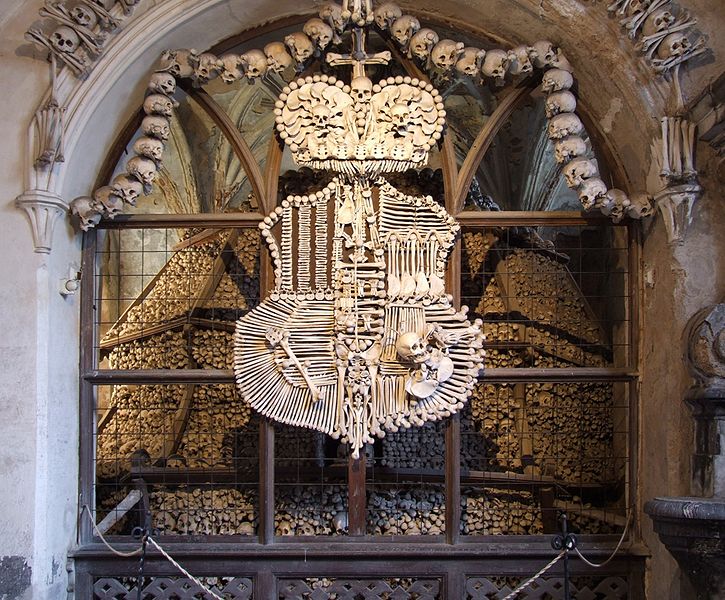

Why are there something like 70,000 people’s bones all gathered together into an arrangement of grisly sculptures in a cellar beneath a small Gothic church on the site of the old Sedlec monastery? Because in 1278, Henry, the abbot of the Cistercians, went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem where he supposedly gathered up a handful of dirt from Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion of Jesus. When Henry returned to Kutná Hora, he sprinkled the dirt over the cemetary at the monastery, and after that it became some kind of prime real estate for grave sites in Central Europe. People from everywhere wanted to be buried there in the blessed soil. When the Black Plague swept through in the 14th century, the graveyard had to be seriously expanded. Good thing it was, because after the Hussite Wars of the early 15th century, they really needed the space. Over time, old graves were exhumed and the ancient bones were placed in an ossuary over which they built a Gothic church around 1400. And over the years all those bones just kept piling up until finally, in 1871, a woodcarver named František Rint, who was employed by the Schwarzenberg family to tidy things up, did something a little unexpected by taking hundreds of thousands of bones and creating a bizarre monument of beauty and death which you can still visit today.

If you’d like to do so, you can catch a train direct to Kutná Hora from Prague Hlavní Nádraží (main train station) any morning, seven days a week. Check out this link for the train schedule.

The coat of arms of the Schwarzenberg family created by bone-stacker František Rint. Photo by Marcin Szala