Part 1 – CZECH EMIGRANTS, Leaving and Returning

During the chaotic history of Czechoslovakia during the latter part of the 20th century, quite a number of its citizens found it necessary to leave, for various reasons, regardless of whatever feelings they might have had towards their homeland. The Nazi occupation of the Second World War, the Communist takeover afterwards, the Soviet invasion of 1968, the bleak gray years of the occupation and “normalization” that followed in its wake, all of these events have given some families ample cause to set out into the world to seek a better life in far-away lands. Some of them have returned since the Velvet Revolution ended Communist rule here in 1989, and some of them have not. I’ve been lucky enough to talk to a number of these people over the past few years and to learn their fascinating stories, and some of them have been gracious enough to let me interview them for this article which will appear in two parts.

1. FROM PRAGUE TO CARACAS – THE RADA FAMILY

Ján Rada was born in Prague in 1946. However, he wasn’t here long before his parents decided to emigrate to Venezuela the following year. Because of growing up in South America and spending much of his life there, he has typically gone by the Spanish name Juan (which is how I know him), although his sister still refers to him as Honza (the familiar Czech diminutive of the name Ján). During his life he has been a sculptor, a self-proclaimed international ‘bum’, a professor of economics, a bank official, and a financier. These days he’s retired and spends about half of every year living in his wife Lise’s native Quebec, and the other half of the year in Prague. Recently Juan and Lise told me all about the history of his family and what happened to them during the Second World War, and why they left Czechoslovakia in 1947. Juan’s sister Maria filled in some of the gaps in their knowledge for me on the telephone shortly after that.

Juan’s grandparents owned a successful farm in a small town called Blovice, near Plzen, which was run primarily by his grandmother, “a very strong lady.” His grandfather “dealt with grain. He had his own wagon in the train and he would ride with the train, and in his pockets he had different strains of the grain. So he would go and … the train would stop at the village or whatever, and his clients would get on the train, to his private wagon, and he would take out from his pocket the seeds and he’d give them samples. And when he would come back, he would talk with these people who already had the seeds about how much they wanted to order of what kind of seed.”

Juan’s father was born Robert Radnicer Gach, not Rada, but eventually, “he changed the name because the name sounded German and he did not want to have anything with the Germans much less a family name.” The reason for that becomes apparent later in the story when one learns of Robert’s experiences during the Second World War.

As a young man Robert traveled to Prague to study medicine, most likely at Charles University, though no one in the family is sure anymore if that was the school where he studied. One evening, while attending a formal dance at the Municipal House in Prague 1, he met Květa Hniličková who was just 16 at the time, and who went on to graduate from the Academy of Arts and became an illustrator and art professor. Unfortunately for them, their blossoming relationship was interrupted by the German occupation of Prague in 1938. As a Jew, Robert soon found himself confined in one of the Prague ghettos.

Květa Hniličková, illustrator, university art instructor, designer, and survivor of both Terezín and Ravensbruck. Photo courtesy of Mélanie Rada.

Květa must have know full well the risk she was taking when she began to help him and his fellow detainees by smuggling food and money to them. Unfortunately for her, she was eventually caught, but fortunately for Robert, the Nazis didn’t know that he was involved and she never told them. After that, Květa was sent as a political prisoner to the “ghetto” at Terezín in northern Bohemia, which was actually a holding camp where Jews and other people considered undesirable by the Nazis were subsequently shipped off to the various concentration camps of occupied Europe. There she was severely beaten and because of that received a head injury which caused a blood clot and calcification in the back of her skull, resulting in recurring migraines which she suffered with for the rest of her life. Eventually, she was transported to the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbruck, Germany, where she remained for the duration of the war.

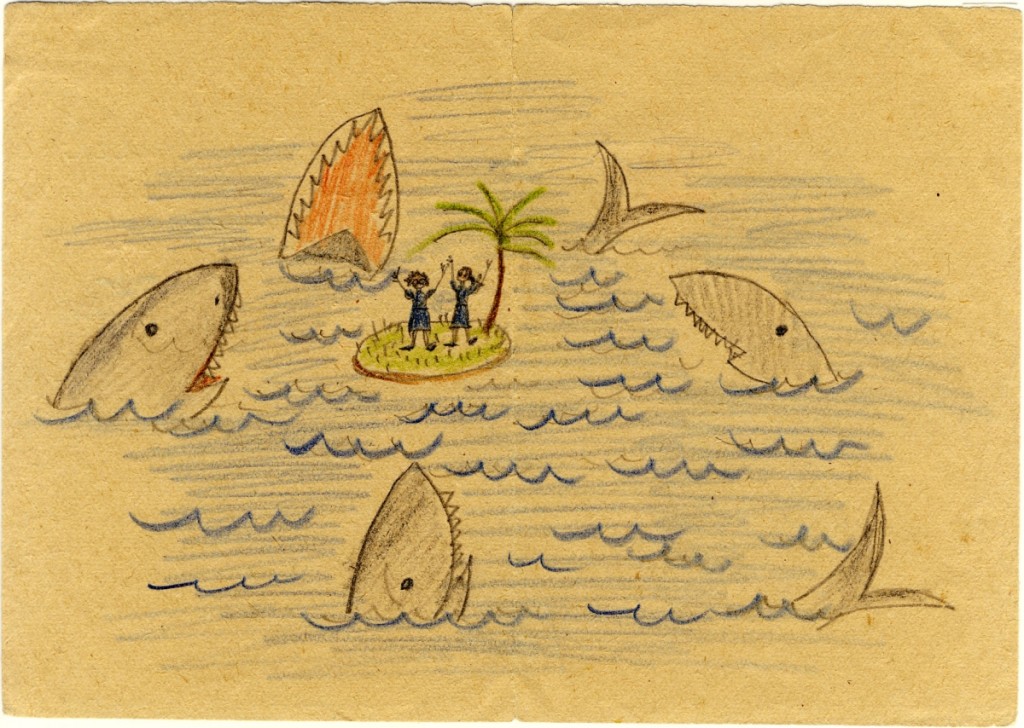

“Our Island”, a drawing from Ravensbruck concentration camp credited to Květa Hniličková.

Robert, in the meantime, was shipped off to a concentration camp himself. Juan’s sister, Maria Radová (whom we’ll get to know better in a subsequent article), tells me that their father was transferred to several different camps during the war, but she’s not sure which ones. Lise believes that when the war ended he was at Auschwitz, and at some point Robert told her that neither he nor the other inmates had any idea of what was going on in the outside world until at last one morning they awoke to find that all the guards had deserted the camp. Soon after, they discovered that the war was over, and that Germany had lost. So Robert, in very poor health by this time, set off walking to find his way back to Prague. No one is quite sure why, but somehow he ended up somewhere in Belgium where he took refuge at a farm because he was almost dead and couldn’t go on any further. He was discovered there by the farmer’s wife, who called the local priest when she found him, who in turn contacted American soldiers who took him to a military hospital nearby where Robert was admitted and where he eventually recovered his health.

Meanwhile, Květa was still in Ravensbruck. When the Allied armies starting getting close to the camp, she and her fellow prisoners were packed into a truck to be transported to they knew not where. While they were traveling in the middle of the night, there was an explosion in the road and during the resulting mayhem Květa and a friend were able to escape. Along with them they took an old woman who was unable to walk, so they transported her by wheelbarrow. They still had no idea what was happening, but eventually they stumbled upon a Russian army camp and were told by the soldiers that the war was ending and that Czechoslovakia had been liberated. Květa then made it all the way back to Prague on foot.

Robert was not there. According to Lise, Květa looked for him and her friends told her that he had disappeared and was probably dead, but she refused to believe it because she said Robert had promised her that he would find her again. And eventually, once he had recovered, he did. They were reunited in Prague in 1945 and married soon after. At the time, in order for that to happen, Robert had to convert to Catholicism. So they contacted a priest they knew, Robert was baptized, and the couple was married.

Robert Rada and Květa Hniličková signing the marriage register in Prague in 1945. Photo courtesy of Mélanie Rada.

Their first child, Ján a.k.a. Juan, was born the following summer. Květa returned to teaching at the art school and she was very happy. Robert took a job as a milk inspector. One could assume that life was returning to something like normal until… the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia won a majority of seats in the parliamentary elections of 1946. According to Juan, his father “had a sense for the political. When he said something was going to happen, it happened. That’s for sure. And he suddenly realized that the Communists were going to take over. So what he did is he immediately tried to get some papers to emigrate.” Robert decided that he wanted to emigrate to the United States for various reasons, but one principal reason is that the U.S. Ambassador at the time was an acquaintance of his. “It was in ’47,” continues Juan, “so he goes to the embassy and asks. He wants to have a visa to the United States. And the ambassador told him that he can get it, yes, but it’s going to take him maybe a couple of weeks. And papa said, ‘We don’t have a couple of weeks because this is going to fall before that time. What is the country which gives the easiest visa here in the Czech Republic, any country?’ And the ambassador said, ‘Venezuela.’ And papa said, ‘Ok, I’m going there. Where’s that?’”

So the plans were laid. The family traveled first to Switzerland to visit Robert’s surviving sister who had spent the war there (his other sister died in a concentration camp, according to Maria). After that they headed to Genoa where they booked third-class passage on the ship Amerigo Vespucci bound for Caracas, Venezuela. When they first arrived, they were assisted for a very short time by a Jewish aid organization and also by the community of Czech immigrants who were also there. Soon they were able to get a room in a pension, and Robert found a job delivering marmalade on a bicycle while Květa went to work designing labels for jars for food products, perhaps even for the same jars of marmalade which Robert was delivering.

After a time they moved to another pension, and then their fortunes really started to change once they met a gentleman named Wenceslaus Hurt who owned an iron works. “For the size of Caracas,” Juan says. “it was a fairly major foundry… And he made lamps, very gorgeous lamps, and doors, and things for the very wealthy in Venezuela. And whenever a Czech did not have where to go, he came to him, and they had a couple of rooms, and these Czechs slept in these rooms til they had enough money to leave. Not only in the rooms, but they would sleep in the woods, anywhere. And he would not only give a place to sleep, but he gave them money. And they had a very small kind of wooden hut which was different from the other ones. And my parents moved into that hut. And my father started delivering the things that Mr. Hurt made, and my mother was designing the merchandise [that was made in the foundry].”

Unfortunately, Mr. Hurt was not in good health. “He had coronary thrombosis and all kinds of stuff. But with the help of my parents, he got more or less well,” and he was able to live for another four years. The Radas helped Mr. Hurt fix up the foundry and pay off the mortgage on the land before it and the iron works were seized by the bank. The land was divided in two and they built a nice house for themselves on the front part, and the back part of the foundry was converted into a house where Mr. Hurt lived. “I would say the concept of ‘poor immigrants’ for my parents stops there.”

Eventually Květa went back to teaching at a university and working as a designer for another company which made lamps. Once their daughter Maria was born, she spent more time as a housewife, but Juan says that she never stopped teaching or designing. In time, after trying a number of different things, Robert started his own property management business. Juan explains, “For Citibank this company was in charge of all the infrastructures, cleaning, servicing the electrical systems, servicing the security systems, managing the garage, managing a cafeteria. It was a company which managed service, maintenance, and more for buildings and it was very, very successful.”

When asked about the role that Czech culture played in their upbringing, Juan tells me that the family spoke Czech at home, though he and his sister both attended school in Spanish. Their parents had many Czech friends, but Juan socialized primarily with other expatriates and native Venezuelans. As a young teenager, after a very few lessons, “maybe ten hours at most,” Juan was sent to a summer camp where he began to learn English. When he returned, he was enrolled in an American-run international school and he continued his studies primarily in English from then on.

I asked Juan if his parents had ever returned to Czechoslovakia. “Yes, in the ’70s they went back to visit. We talked a lot about it and basically, what they saw, they expected. A country under Communist rule.” And Lise added, “They were happy to be in Venezuela.” Juan concluded, “They said they would never live in [Czechoslovakia].”

Juan also traveled to Czechoslovakia during the ’70s and he told me what he’d observed there. “In 1970 there were no restaurants like you and I know. There were these places which sold bread and cheese and meats, very inexpensive. But it was very nice. I enjoyed it very much. And yes there were the Communists there, and you had to be very careful about talking about the Communists. But when you went into the house of somebody, they talked openly, and they cursed the Communists. I felt that they were much better off than they made us think compared to Venezuela. Ok, so they did not have liberty. But everybody had food. Everybody just about had a car, and everybody had a television. It was illegal to look at western programs. That was totally dangerous. But everybody did. The Czechs are very good at doing this kind of subversive thing.”

And what does he think of the Czech Republic today? “There is no comparison… You have people with [a] better quality of life than most of the westerners, however still thinking the West is better.” He finds that puzzling, as do I. Well, as they say, the grass is always greener…

Robert Rada passed away and was buried in Caracas in 1981. After he died, Květa visited their homeland again two or three more times after the end of Communism. Their daughter Maria had moved to Prague in the early 1990s. At the end of every visit, Květa always went back to Venezuela. But the last time she came to Prague in 1996, she was starting to think about the idea of staying here with Maria. According to Lise, she never completely decided. But as fate would have it, Květa passed away unexpectedly before she ever had a chance to return to Caracas. She was buried in the family plot at a large Prague cemetary. Sometime later, Juan brought his father’s ashes over from Venezuela, and they were laid to rest in the same family plot with Květa’s in a receptacle that Lise, a talented ceramist, made for them.

This is the first article in a series on Czech emigrants which will appear in the Prague Extravaganza Tours blog over the next few weeks. I would like to thank the Rada family, Juan, Lise, Maria, and my wife Mélanie, for sharing their family’s history.