THE PRAGUE SPRING AND THE SOVIET INVASION OF 1968

In the late-night hours of 20-21 August, 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was invaded by approximately 500,000 members of the combined armed forces of East Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland lead by – who else? – the USSR. This military incursion was undertaken by the Warsaw Pact nations in order to put a stop to the so-called Prague Spring which had been ushered in by the radical reform policies of Czechoslovak Communist Party leader Alexander Dubček, and it began one of the darkest periods of the 20th century in this country’s history. The USSR’s ambassador to the United Nations called the invasion an act of “fraternal assistance”, and Soviet soldiers occupied Czechoslovakia from that time on until after the end of Communism in 1989.

A well-known joke of the period went something like this: “What are the Russians to the Czechs, our brothers or our friends? Our brothers, obviously, because you may choose your friends.”

Peaceful obstruction and resistance to the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968.

One way you can learn more about this era of life in the former Czechoslovakia is by going on our COMMUNISM & BUNKER TOUR, and also, since this weekend marks the 48th year since the invasion, I’d like to use our blog space this week writing something about it.

The period of social, political, and economic reform known as the Prague Spring was a long time coming, a consequence of events that had been unfolding almost since the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia after the Second World War. In 1949 the Soviet Union created the Council for Mutual Economic Assitance, or CMEA, in order to guide and coordinate the economic relationships between the other Communist countries of the Eastern Bloc. The CMEA decided that Czechoslovakia would be a center of heavy industry and machine building. Though the ever-expanding military was able to consume about one third of the total production of the industrial sector, Czechoslovakia found itself cut off from many of its Western trading partners as the 1950s wore on and the Cold War intensified. Production capacity far outstripped both domestic demand and the supply of raw materials. At the same time, the emphasis on heavy industry and military provision soaked up so many resources and so much manpower that there was very little left to put into the supply of consumer goods and services. Additionally, the Communist government undertook a program of currency “reform” that had the end result of wiping out most people’s savings. Add to all of this the general atmostphere of political repression, party purges, and show trials which lead to the imprisonment of something like 200,000 people, and you can see that things were not going all that well for the common folk of Czechoslovakia in the 1950s.

During the 1960s things started to get better, but the pace was slow. The worst purges and persecutions of the Stalinist period had come to an end and life was generally more secure, though political arrests still occurred relatively frequently. Censorship of the press and the airwaves was still strictly enforced. Food production had increased and even surpassed the levels of the pre-war period, and most families had by then recovered from the shock of the currency “reform” and were even able to save a little money. But there wasn’t much to spend it on. Automobiles and other durable consumer goods were in short supply and travel was restricted. In the mid-60s there was an attempt at economic reform by adapting socialist planning to the market forces of supply and demand, but little came of it and the process was scrapped without ever being fully implemented by the responsible commission. All the while, popular discontent was rising…

By 1967 the Communist party was having internal difficulties as well resulting from power struggles between the old guard and the new, and by a perceived antipathy towards Slovaks and Slovakia on the part of Antonín Novotný, who was at the time both Communist Party First Secretary and President of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. As support for Novotný began to slip away and the upper echelons of the party were falling into disarray, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev was asked to visit Prague in order to advise in the disputes. He arrived in December, evaluated the situation, and concluded that Novotný would have to step down from his post as First Secretary. On 4 January, 1968, Alexander Dubček, leader of the regional Slovak Communist party,was named as his successor.

The USSR considered Dubček an acceptable choice. He had studied at the Higher Party School in Moscow, was fluent in Russian, and had lived in Russia for a number of years as a child. He had been a member of the Czechoslovak party’s central committee and leader of the Slovak regional party since 1962. Dubček was seen as a staunch party supporter and a committed Marxist, all of which was true, but his devotion to socialism was about to manifest itself in a way that the Soviets hadn’t foreseen and, in the long run, would not tolerate.

Alexander Dubček winning the people’s approval.

Unbeknownst to the Russians, Dubček intended a complete program of reform within Czechoslovakia. He felt that Communism needed to move forward with the modern world and leave the violent excesses and iron-fisted rule of the Stalinist era far in the past, in the process creating a true workers’ paradise where the disparity between how the system was supposed to work and how it actually did work would be eliminated. Since socialism had been considered officially achieved in the country for many years, Dubček believed that heavy-handed political repression and censorship were no longer necessary, and that workers should be allowed some freedom of entrepreneurship within the structure of the socialist economy.

The first big step came at the beginning of March when Dubček‘s leadership took away control of radio and television from the Main Adminstration of Press Supervision, and decreed that editors-in-cheif were strictly responsible for the content of the mass media. This measure effectively dismantled prior censorship, even though no official announcement was made about it until June. Tentatively at first, and then with increasing frequency and confidence, radio and television broadcasts began discussing formerly taboo subjects and becoming critical of both the party and the government. There was a freer flow of information about the world and what was happening outside the country’s borders, and international events were discussed with more and more openness.

Towards the end of March, Antonín Novotný finally stepped down from the presidency and was then officially expelled from the Communist Party. He was replaced by Dubček ally Ludvik Svoboda, followed also by changes of the prime minister and speaker of the national assembly. Once the new leadership was in place in April, they came up with a blueprint for their new policies called the Action Program which was approved by the National Assembly at the beginning of May. The new Action Program made a legal guarantee of “freedom of speech for minority rights and opinions”, called for the rehabilitation of many of the victims of the purges and arrests of the 1950s, and enabled freedom of movement and travel abroad for common citizens. The economic policies outlined in the Action Program included the liberalization of foreign trade and a reduction of the role of the state in economic planning. Some small-scale private enterprise was to be allowed, and though larger businesses were to remain nationalized, their direction and operation was to be decided on by workers’ councils. But despite all of this loosening of control, the Action Program in no way envisioned or was intended to precede a disruption of the primacy of the Communist Party. Czechoslovakia would remain a socialist country but, in the words of Dubček, it would be “socialism with a human face”.

After an initial period of reserve, the public was highly enthusiastic and approving of the new policies. The media actively encouraged and engaged in open debate and discussion of society’s concerns, and intellectuals made statements supporting the reforms and calling for additional democratization. People freely discussed their thoughts and opinions at home, at work, and on the streets for the first time in many years, and a number of non-party-affiliated activists groups sprang up. It seemed that the long winter of Cold War Communism was reaching its end, and the warm breezes of a Prague Spring were thawing out the hearts and minds of the country.

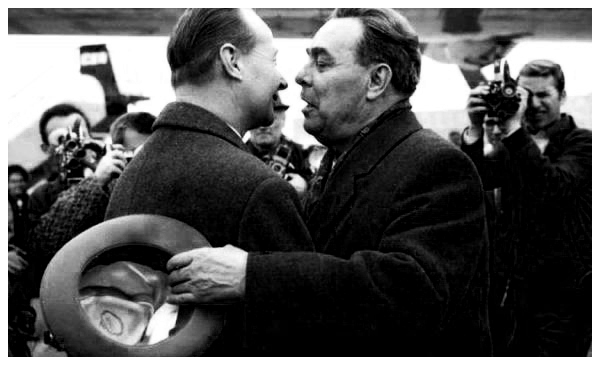

Dubček and Leonid Brezhnev of the USSR.

Needless to say, this was all quite disturbing to the ruling regimes of the other Eastern Bloc countries, who began applying pressure on Dubček’s government at a Warsaw Pact meeting in Dresden in late March. The Czechoslovak delegation was surprised to find that their country was the main item on the meeting’s agenda. The Soviet Politburo and the delegations from Poland, East Germany, and Hungary all expressed their dismay at the recent repeal of censorship in Czechoslovakia. In the form of a veiled threat, Brezhnev told Dubček that he hoped that Dubček would have “the desire, the will, and also the courage to implement the necessary actions” to prevent the situation of from deteriorating any further.

In early May, after the beginning of the implementation of the Action Program policies, Dubček was summoned to Moscow and grilled by the Politburo about what specific actions his government intended to take to head off a full-scale counter-revolution in Czechoslovakia. Dubček and his delegation did little more than reassure the Soviets that they were firmly in control of the situation, after which they were made to agree on a date for joint military exercises in Czechoslovakia that summer. The exercises, code named “Šumava”, were held at the end of June and involved some 24,000 men including some 16,000 members of the Soviet armed forces. However, when the exercises concluded on 30 June, the withdrawal of the Soviet forces was long and slow and dragged on until the beginning of August, and they left their signals network in place when they finally left.

In the first days of July, the Politburo summoned the leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist party to a meeting in Warsaw, but Dubček refused to attend. The Warsaw Pact allies met without them and drafted a strongly worded letter voicing their concern and consternation about the developing sitation in Czechoslovakia which was delivered to Dubček by the Soviet ambassador later in the month. Finally, the Czechoslovak leadership agreed to two meetings in Slovakia at the end of July and beginning of August, but little was accomplished at either of these, and the Warsaw Pact powers came to the conclusion that Dubček was not to be trusted any longer. It didn’t help Dubček‘s position that sometime during the second meeting, Czechoslovak party official Vasil Bil’ak passed a secret letter to the Soviet delegation which was signed by five hardline Czechoslovak central committee members calling on the Soviets to come to their aid “with all the means at your disposal”. And so the Soviet leaders began planning their military intervention.

Fraternal assistance?

When the invasion came, it was swift and decisive, involving some half a million Warsaw Pact soldiers from five countries, 6000 tanks, and 800 airplanes. On the night of 20-21 August, Soviet paratroopers were dropped at Prague airport and at other strategic locations where they surrounded Czechoslovak barracks and confined the troops within. The airport was seized as a staging area for further air deployment, and major media and mass communications enterprises were seized, including Radio Prague and Czechoslovak Television. Meanwhile, tanks and soldiers were pouring across the border at various locations and seizing strategic sites nationwide. The invasion had been timed to coincide with a meeting of the Presidium of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, which was also surrounded and detained.

During the invasion 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed and another 700 wounded, a casualty figure that would have been much higher but for the fact that they had been instructed not to resist the invaders. The Soviet forces lost 98 soldiers but, according to some sources, their deaths came about largely from mishandling their own weapons, car accidents, and plane crashes.

Fraternal resistance.

The reaction of the general population was nonviolent, but it was anything but passive. Townspeople and villagers did anything they could to confuse and disorient the invading armies and to disrupt their communications. House numbers, street signs, and road signs were painted over, removed, or changed around, except the ones which pointed the way back to Moscow, and people everywhere took to the streets in protest. In general, any interactions with the invaders were undertaken in a completely non-cooperational manner. Russian language lessons were compulsory in schools at the time, and many Czechs and Slovaks put their knowledge of the language to good use, arguing and debating with the invaders, and printing posters and flyers in Russian which condemned the invasion. Many of the Warsaw Pact soldiers were confused by the situation they found themselves in as they had been briefed that they were going into Czechoslovakia to suppress an armed counter-revolution, and when they got there, of course, they found that there was nothing of the sort going on. Many on the front line had to be replaced once they discovered that their opponents were simply their brother and sister workers, and subsequently lost faith in their mission and became an unreliable force of oppression.

In the end, there was nothing for the government and the citizens of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic to do but recognize the fact that Dubček‘s grand experiment in “socialism with a human face” was over, and that the occupation force was there to stay. Dubček and other top officials were taken into “protective custody” and spirited away to Poland where they were held for a time until they were moved to Moscow. After several days, a delegation lead by President Svoboda flew to Russia to secure their release and then negotiations began about the dismantling of the system of newly instituted freedoms that had so recently been installed. Then began the long months and years of “normalization”. The Prague Spring was over, and the gray winter of the Cold War was back again and lasted for another two decades.

Alberto Guerendiain.

I BORN AND LIVE IN ARGENTINA. The histoy of the Prague spring is so interesting for me, I really do not know all the details mentioned in this article.

I will visit Prague with my wife next March 30 for 4 days and I will do the communism city tour to know more about your Republic.

Best regards, Alberto Guerendiain

Dear Alberto,

you are very welcome to join our Communism & Bunker Tour at the end of March. We run this walk every Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday at 11 AM, meet the guide at the Powder Tower in the namesti Republiky. The guides will be holding a blue umbrella with white clouds. I am sure that you will learn a lot about the politics, normal life and paranoia on this 3,5-hour tour. The highlight will be the visit of nuclear shelter under Vaclavske Square and Kofola drink in the old-school canteen. Please make the reservation here: https://extravaganzafreetour.com/communism-bunker-tour/

Enjoy your trip!

Klara, founder & guide